thought is hinge and swerve...

ten poems for changing eye and hand

Jane Hirshfield

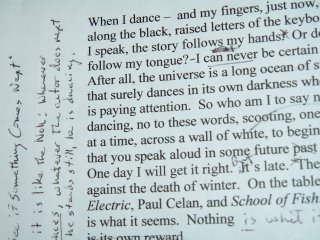

Articulation: An Assay

A good argument, etymology instructs,

is many-jointed.

By this measure,

the most expressive of beings must be the giraffe.

Yet the speaking tongue is supple,

untroubled by bone.

What would it be

to take up no position,

to lie on this earth at rest, relieved of proof or change?

Scent of thyme or grass

amid the scent of many herbs and grasses.

Grief unresisted as granite darkened by rain.

Continuous praises most glad, placed against nothing.

But thought is hinge and swerve, is winch,

is folding.

“Reflection,”

we call the mountain in the lake,

whose existence resides in neither stone nor water.

*

This poem is only one marvelous wrinkle in After, Hirshfield’s brilliant collection (HarperCollins, 2006). The volume is one of the strongest books of poetry in many years. If you read it, you will find yourself in the pages.

With “Articulation: An Assay,” I’m fascinated with Hirsfield’s filter of Zen in the resistance of an urge to change all things around us. The monumental aspect of this difficult truth is in the universality of all. The “what-if” of allowing life, in the grandest sense, to run its course. We all seem to possess the inclination to fix for the better – or so we believe – objects, people, and situations around us. This poem cuts against that capacity and finds itself philosophically in tune with James Wright’s vision of the “hammock” approach to life. Change does happen, but is viewed as a natural process. There’s the greatness. Hirshfield writes such tempting lines:

What would it be

to take up no position,

to lie on this earth at rest, relieved of proof or change?

This is a letting go, a surrender of the self. Because of the nature of our world, most actions are motivated outside the self. We attempt to justify those actions to self … or attempt, in vain, to believe that we do what we want to do. And I can hear the rumblings in your brains … even now. Yes. Mother Teresa was a person of greatness. Yes, she sacrificed self. Yes, she did good things. But, her actions – at least in part – were motivated by the need itself … or by her own image of the self she created … or were motivated by the world’s expectations – and here read “the suffering and the helpless” and those of us not suffering who looked to her for guidance or who viewed her as the one who could help. In the end, none of that takes away from her gift.

Hirsfhield’s poem ends with a powerful image that is focused between two worlds. In Buddhist thought, it’s not the moon and not the water, but is the moon in the water that is life-impacting. When Hirshfield uses the word “existence” – or being could be another flavoring – she recognizes that there’s a certain reality that does not rest in the doing or in the not doing … a reality not found in bad actions or in the cessation of those actions. Given her Zen background, Hirshfield must surely encounter the dilemma of the good. We see bad things happening and we feel, without fail, an urge to put an end to those things. And that quest is a consuming quest. The truth – like “the mountain in the lake” – lies shimmering somewhere between the two extremes.

2 comments:

The one that really stuck in my head from that book is "Hope: An Assay," so much shifting in eight lines. I blogged about "After" a while back and spent a bit of time discussing "Hope."

There are so many good pieces in her collection. Thanks for the read, Andrew.

Post a Comment